Site Visit: Dark Energy Survey at Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory

Vicuña, Coquimbo Region, north-central Chile

December 8-14, 2018

This World: A Poem for the Dark Energy Survey

Where to read

Excerpts of This World: A Poem for the Dark Energy Survey, appear in the following publications and venues under its preliminary title, At the Edge of the Abyss:

Milky Way and Victor M. Blanco Telescope, Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory, Chile, 2018, photo by/courtesy of Satya Gontcho A Gontcho

THIS WORLD: A Poem for the dark energy survey

I hear

the verse of someone.

It swells in the night

like a dune.

—Gabriela Mistral

“Midnight” (1961), tr. Doris Dana

Joshua A. Frieman and Amy Catanzano, Victor M. Blanco Telescope, Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory, Chile 2019, photo by/courtesy of Robert Morgan

INTRODUCTION: DARK VISION / FIRST LIGHT

This World draws from my exploratory research of astrophysics at the Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory in the Andes mountains of north-central Chile, where I worked with the Dark Energy Survey, an international collaboration of scientists that study dark energy and its role in the 13.8-billion-year history of cosmic expansion. It also draws from my cultural research on the indigenous Aymara nation in the northern Andes and Altiplano regions of Chile, Bolivia, and Peru, which I conducted in Santiago with the literary scholars Daniel Castelblanco and Andrea Echeverría, colleagues of mine at Wake Forest University. “Cerro Tololo” means “mountain at the edge of the abyss” in Aymara.

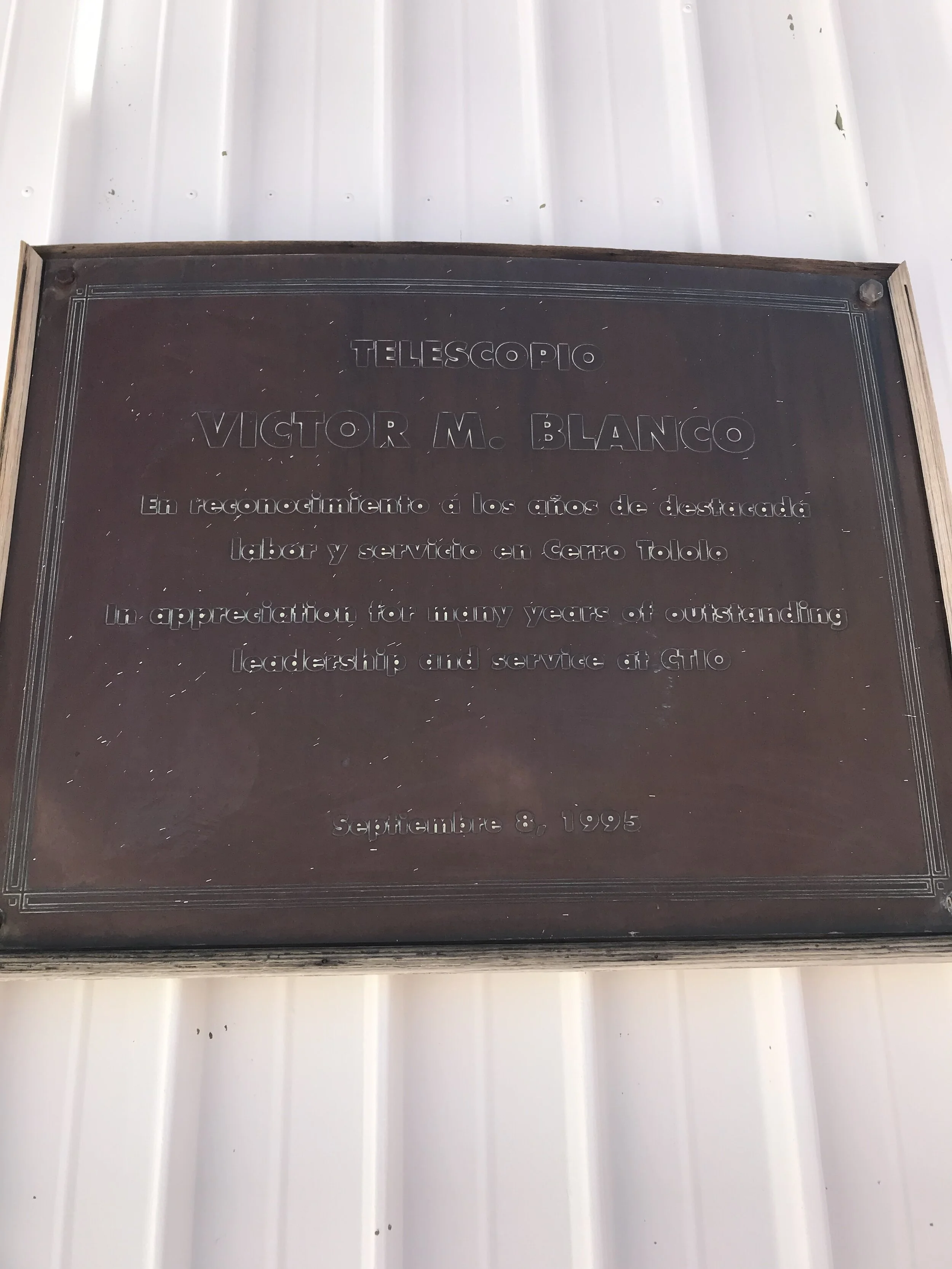

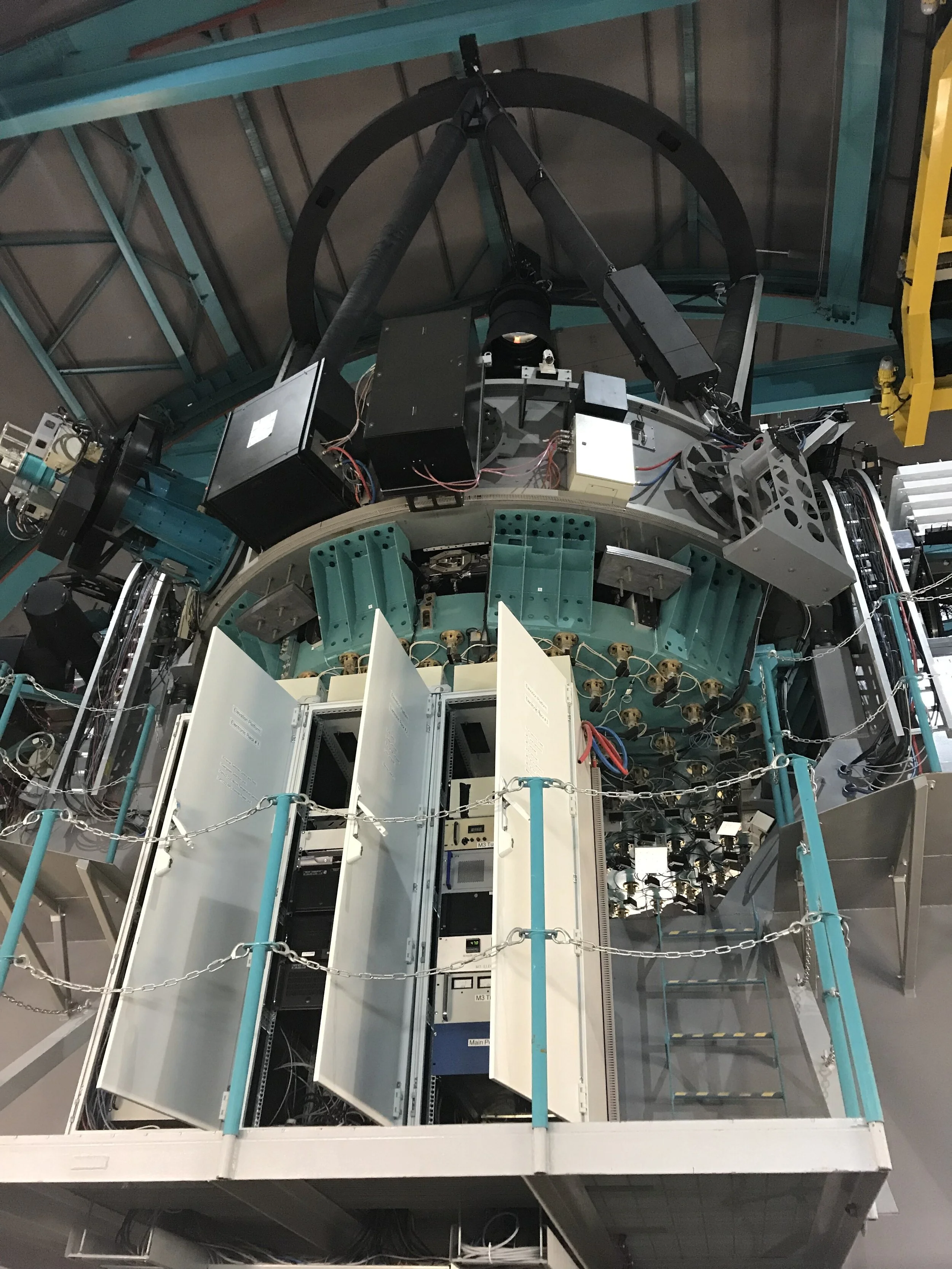

At Cerro Tololo, I was immersed in a multimodal investigation—directed by my poetics—on the nature of dark energy, a nonluminous phenomenon that scientists believe composes 75 percent of the known universe. While my work was centered on my conversations with scientists and our nightly astronomical observations that we conducted inside the Victor M. Blanco Telescope at the observatory, I drew from all aspects of the site visit for this project. The book’s title, This World, draws from the Andean conception of physical reality—what Western science would call spacetime—which has three fluid, spatial thresholds: world above, world below, and this world.

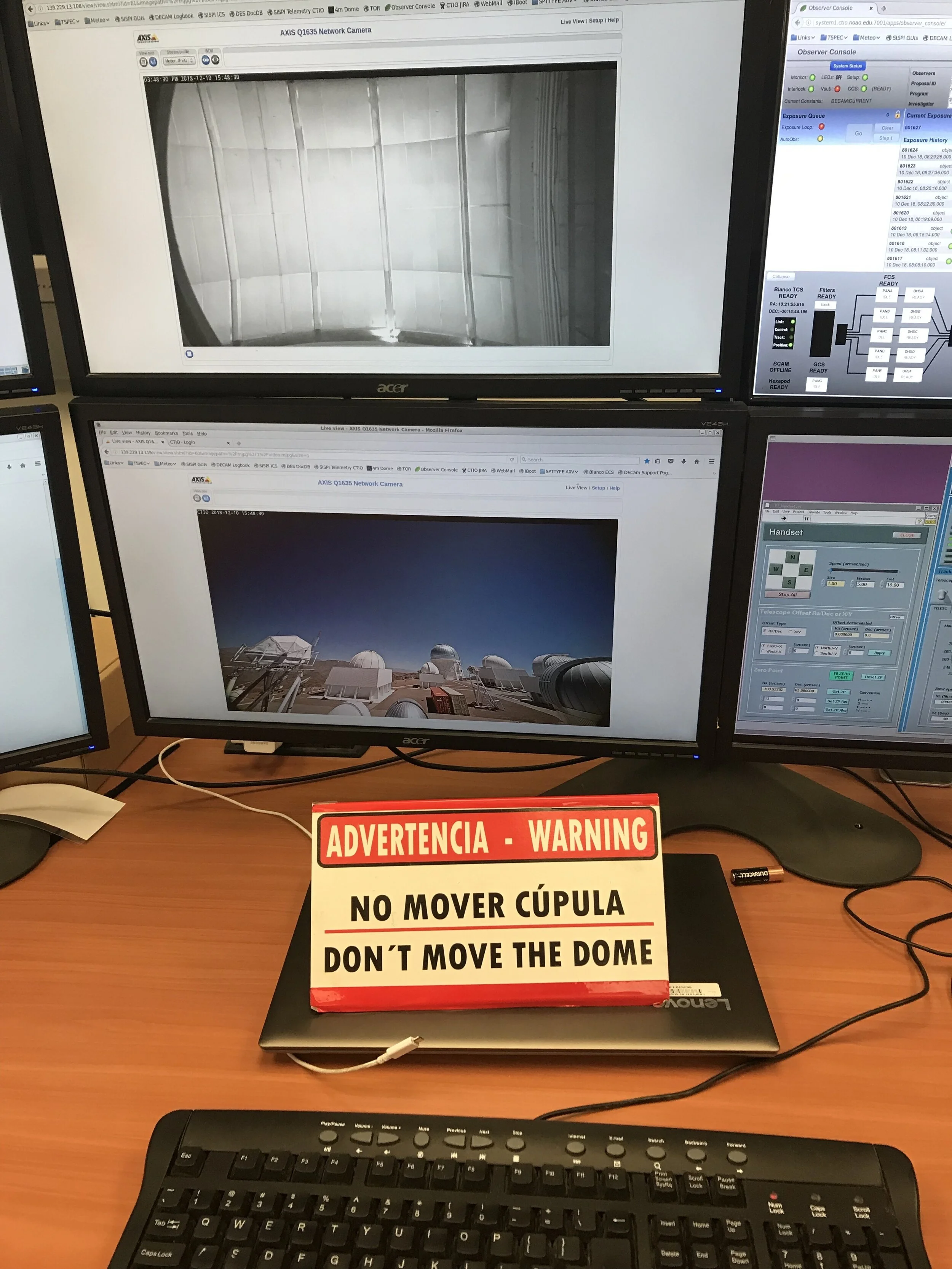

In the control room of the Blanco Telescope, I was awed by the confrontation with deep space and deep time as we viewed millions of distant galaxies that the telescope was live-imaging just above us. I also loved being part of a team. I felt like the resident poet aboard a starship of space explorers. We were indeed on a kind of ship, one sailing not for colonization or capital but knowledge, steered by an international crew navigating an extraordinary vessel docked on a mountain. Like other scientific endeavors rooted in pure research as opposed to military and commercial aims, the purpose of this voyage was to explore the compelling mysteries of our universe. I also participated in profoundly moving outdoor stargazing sessions on Cerro Tololo, protected from light pollution as the Gabriela Mistral Dark Sky Sanctuary, named after the Chilean poet and first Latin American Nobel Prize recipient in Literature from the nearby town of Vicuña.

The region where Cerro Tololo, just south of the Atacama desert, was first inhabited by the Diaguita and Molle cultures from 300 to 700 CE and the Diaguita and Las Ánimas cultures from 800 to 1000 CE. It was later controlled by the Incan empire, which dominated the eastern Diaguita region, and subjected to colonial rule by the Spanish until 1810, when Chile gained independence. Now a center of global astronomy, Cerro Tololo was the first of the large observatories constructed in the Southern hemisphere.

Unlike some scientific research sites that are built without appropriate collaboration with native populations, Cerro Tololo is an internationally cooperative effort initiated by Chileans. First envisioned by Chilean scientists at the University of Chile in the late 1950s, Cerro Tololo was developed by the University of Chile, the University of Chicago, the University of Texas, and the Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy (AURA) under the auspices of the U.S. Air Force and later the U.S. National Science Foundation. It was established between the University of Chile and AURA in the 1960s. When AURA purchased the land for Cerro Tololo from the Chilean government, some of the subsistence farmers and goat herders remained, though most eventually left for jobs in nearby towns. The region now has environmental protections and few inhabitants, creating a largely intact desert ecosystem that supports native plants and animals such as the jackrabbit-like viscacha.

About the Dark Energy Survey

The portion of outer space observed by astronomical sky surveys such as the Dark Energy Survey is known as that survey’s “footprint.” The Dark Energy Survey conducted two surveys at Cerro Tololo: a wide-area survey, imaging a large portion of outer space, and a time-domain survey, covering a small portion of outer space but with a large number of images. Its footprint for the wide-area survey was 5,000 square degrees of contiguous outer space, each part observed in five filters that span different colors of light.

Galaxy NGC 1365, from the Dark Energy Survey’s first light, courtesy of Joshua A. Frieman

At Cerro Tololo, the Dark Energy Survey took images of massive structures in the universe to study galaxy clusters, distant supernovae, and primordial sound waves. They also studied the degree to which light from galaxies is bent by gravitational lensing, where light emitted by galaxies is distorted by the gravitational pull of massive objects. This research has enabled them to investigate how the universe itself has evolved by their measurements of the rate at which the universe has been expanding at different times in its history. They are using this knowledge to construct an important, high-resolution map of the known universe. Knowing more about the rate at which the universe has been expanding also tells them more about dark energy, theorized by scientists to be responsible for the universe’s evolution or growth over time. The scientists of the Dark Energy Survey took their images with an extremely sensitive camera, DECam, which they built in different countries, assembled at Fermilab, and mounted on the Blanco Telescope at Cerro Tololo.

Victor M. Blanco Telescope, control room, Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory, Chile 2019.

While the major discovery of cosmic acceleration—that the universe is expanding at an accelerating rate—was made over twenty years ago at Cerro Tololo by a different team of scientists, what is responsible for the expansion of the universe remains a fundamental question in science today. Physicists largely theorize that dark energy causes cosmic acceleration, though the exact nature of dark energy is not understood.

The universe, scientists propose, is composed not only of 75 percent of nonluminous dark energy but also 20 percent of nonluminous dark matter and only 5 percent of luminous matter that can be seen. As a term, “dark energy” signifies what is invisible or unknown; it may not be energy at all, though it is dark in that it does not emit light. As opposed to ordinary gravity that holds matter together, dark energy exhibits what is described as a “uniform, negative pressure,” which is known as the “cosmological constant” in Albert Einstein’s theory of general relativity. This negative pressure acts as a repulsive form of gravity—a kind of countergravity—at large, galactic and intergalactic scales, pushing matter apart. More space is forged between galaxies and thus a bigger universe.

While dark energy affects large-scale matter in the universe, it is thought to have no significant effect within gravitationally bound systems such as planets like Earth. In addition to the possibility of being a different way that gravity behaves at cosmological scales, dark energy could be the underlying vacuum energy that exists everywhere. It also could be a new kind of field or force, a new particle known as “quintessence,” or something else. Someday, dark energy may tear the universe apart by overcoming the gravity that holds matter together. It is also possible that its behavior may change, resulting in the universe no longer expanding, which could make the universe contract in on itself. Since dark energy is so deeply connected to the physical evolution of our universe as well as its potential destruction, it is a significant area of cutting-edge scientific research today.

On Science and Poetry

Scientists and poets often share a commitment to inquiry, a capacity for wonder, and an instinct toward curiosity. The mission of the Dark Energy Survey speaks to what is central to not only science but the literary arts: humanity’s exploration of the unknown. Much like the literary arts, scientific research draws from inferred knowledge that relies on rationality intersecting with imagination rather than empirical observation alone. Additionally, scientists, like poets, invent technologies to access what lies beyond ordinary knowledge and experience. For poets, these technologies are our poems, built from creative methodologies that engineer language beyond what is ordinary. When we look into a telescope, we are looking back into time. Considered through the artistic lens of poetry, a telescope is a time machine, letting our eyes see into the past through space. A poem, too, is an advanced machine of spacetime, one that enables the reader and writer to alternatively travel.

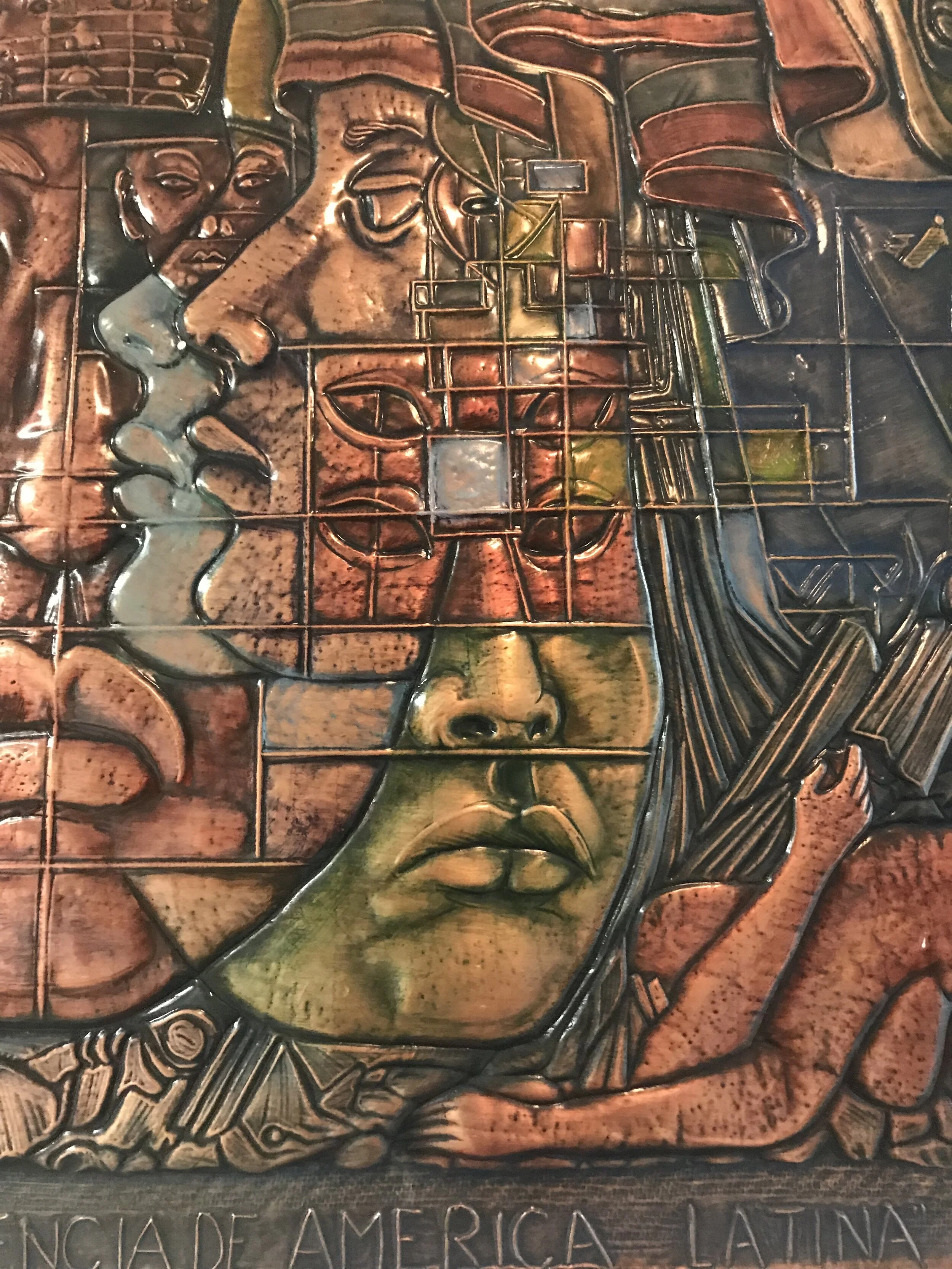

Carolina Musalem, collage in meeting room of Victor M. Blanco Telescope, Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory, Chile 2019.

About the Site Visit to Cerro Tololo

It was through my colleague, the transmedia artist Lynn Book, that I first became acquainted with the astrophysicist Josh Frieman, the longtime director of the Dark Energy Survey affiliated with Fermilab and the University of Chicago. Just before I began teaching at Wake Forest University, Lynn had invited Josh to participate on a panel with the poet and filmmaker Abigail Child, where they discussed the idea that astrophotography was art. Before Josh and I were introduced by Lynn, I read his article, “Seeing in the Dark,” about the Dark Energy Survey in Scientific American: Physics at the Limits. I had bought the magazine that following April to read during my first research trip to CERN in May. I had no idea that two years later, in the Blanco Telescope at Cerro Tololo, I would be joining Josh and looking at live images of distant galaxies, the kinds of images he had discussed with Abigail a handful of years before, debating if they were art.

After my first research visit to CERN, I pursued another grant from Wake Forest, this time to conduct research on the Dark Energy Survey at Cerro Tololo, whose live astronomical observations were soon ending. When awarded the funding, I contacted Josh through Lynn and asked if he might be interested in supporting my visit. He not only agreed but said that he would be there, too. As we coordinated my trip with Steven Heathcote, then the director of Cerro Tololo, I was invited to participate in a cultural-exchange program, led by telescope engineer and project coordinator Javier Rojas, where I would give two talks and poetry readings, one at the observatory inside a meeting room in the telescope and one in La Serena, Chile, where the observatory is overseen.

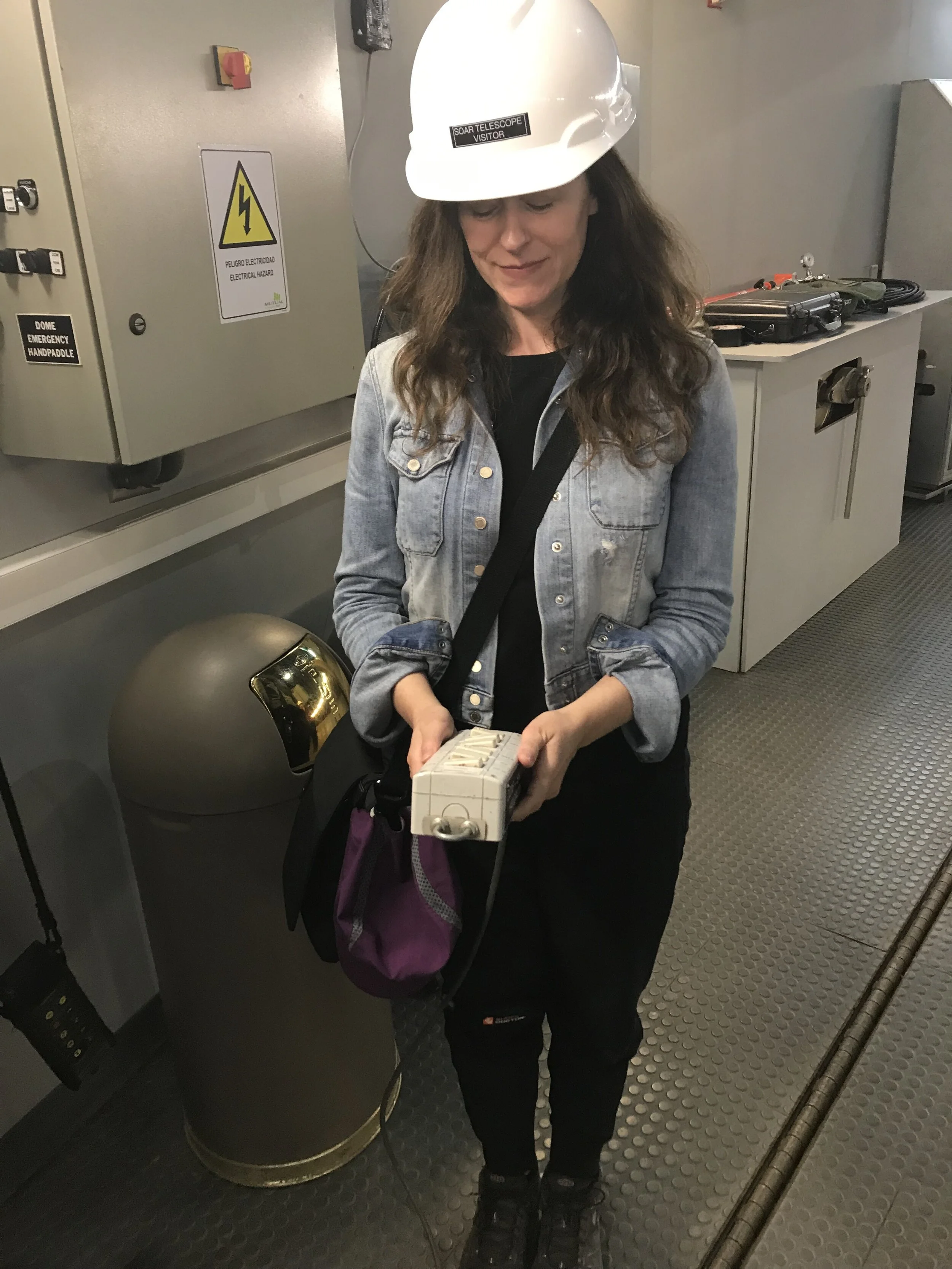

My journey to Cerro Tololo began with a flight from the United States to Santiago and another flight north to La Serena. The next morning I boarded a van that traveled a winding and established but mostly dirt road, climbing two hours up the Andes to Cerro Tololo. Stepping out of the van, I was in the quiet presence of a blue sky overlooking mountains on all sides. The white telescopes gleamed up the hill. I checked into my lodging where visiting astronomers stay. In the sunny, window-lined cafeteria, I soon met Josh and others, including the astrophysicist Satya Gontcho A Gontcho.

I was soon learning from Josh about scientist Fritz Zwiki and his discovery of the relative motion of galaxies. While examining a galaxy cluster in 1933, Zwiki reasoned that the motion of galaxies was going too fast for them to be held together in the galaxy cluster without the existence of more matter, which could not be seen. If there was more matter, Zwiki thought, then there would be enough gravity to hold the galaxies in their clusters. This invisible matter that must hold galaxies in galaxy clusters was first theorized by scientists to be dark matter and later dark energy, Josh told me. That night, in the control room of the Blanco Telescope, I saw for the first time live images of countless galaxies and galaxy clusters, their light finally reaching Earth, caught in the telescope above us by the special camera built by the Dark Energy Survey to see what cannot be seen.

Dark Vision/First Light

In astronomy, “first light” is the first image that a telescope takes. At Cerro Tololo, when I asked Josh if he had a favorite image captured by DECam , he sent me a photo of Galaxy NCG 1365, the Dark Energy Survey’s first light. Known as the Great Barred Spiral Galaxy, the galaxy is located fifty-six million light years away from Earth in the Fornax (“furnace”) constellation. In the tradition of visual poetry that is more artistic than linguistic, more suggestive than descriptive, This World is physically shaped to echo the shape of the Great Barred Spiral Galaxy. The poem enters the Dark Energy Survey’s first light through one spiral arm and leaves through another, both arched toward the spiral center by gravity.

The wondrous work of the Dark Energy Survey, in probing the nature of dark energy by mapping galaxies and other structures through their traveling light, is aided by science and the poetic imagination. Science, like the literary arts and other artforms, operates far beyond the strict realisms of observation, guided by the senses, by using extrapolation, abstraction, and uncertainty as modes of investigation. At Cerro Tololo, on the mountain at the edge of the abyss, different methods of approaching knowledge coexist. The seen and unseen merge together in a dark vision, one that sees what is not seen by seeing differently, and one that travels faster and farther than ordinary perception guided by ordinary language. Dark vision does not stop at the edge of the abyss at Cerro Tololo. Dark vision travels past the abyss, which is not nothing but an open border into possibility. I know this world, because I go there, past the edge of the abyss, where poetry exists.

Works Cited

Dark Energy Survey website, accessed January 3, 2020 < https://www.darkenergysurvey.org>: information on the survey, press releases, articles, and academic papers.

Victor M. Blanco, Brief History of the Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory (1993), accessed Aug. 26, 2020 <http://www.ctio.noao.edu/noao/content/CTIO-History>.

Joshua A. Frieman: conversations, Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory, Chile. Dec. 9-15, 2018.

Joshua A. Frieman, email. Jan. 5-Feb. 25, 2018.

Joshua A. Frieman, “Seeing in the Dark,” Scientific American, Physics at the Limits (Winter 2015).

Clive Ruggles, “UNESCO Astronomy and World Heritage, Windows to the Universe: AURA Observatory, Chile.” UNESCO Astronomy and World Heritage, accessed Aug. 26, 2020. <www3.astronomicalheritage.net/index.php/show-entity?identity=59.>.